Seirocrinus subangularis

100 x 560 cm, 29.8 kg

Lias epsilon, Fleins; Holzmaden

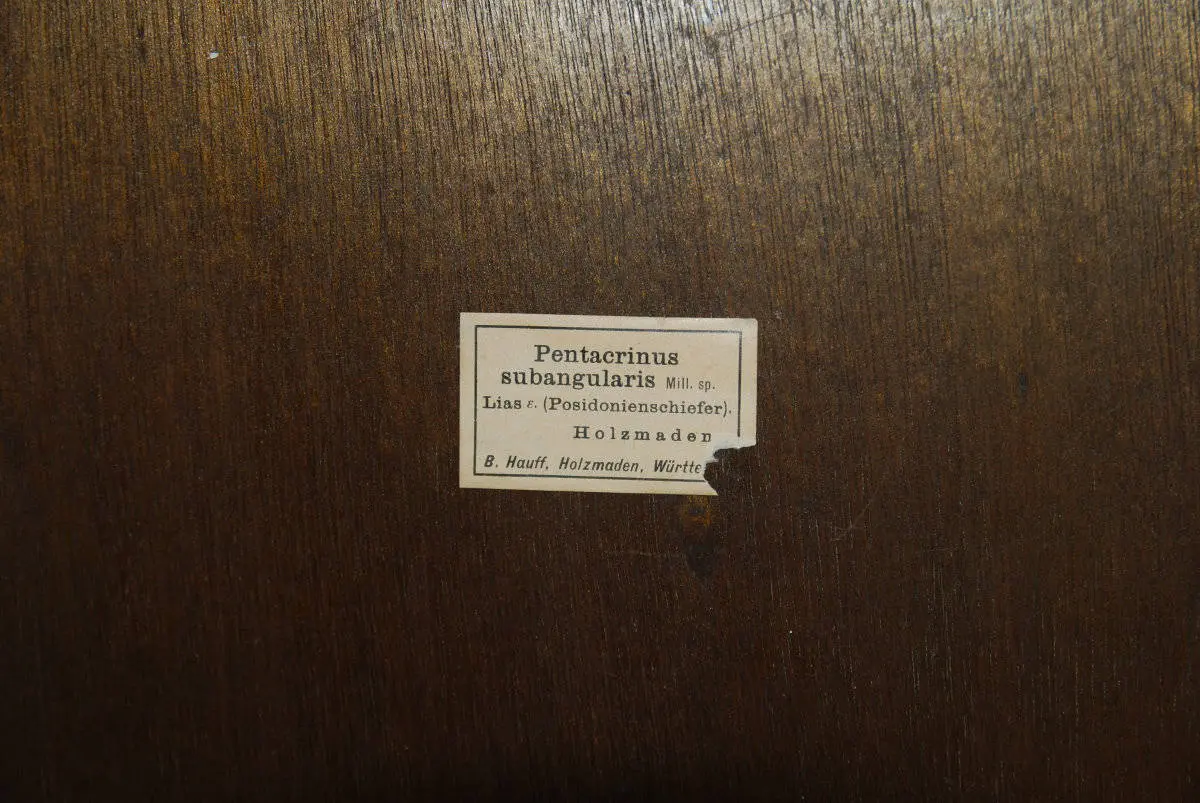

Antique piece from the Hauff workshop

An unusual, decorative piece with historical flair – manually prepared and mounted in a wooden frame, according to the previous owner in the family for at least 80 years.

The large crown tapers upwards towards the outstretched arms in the original plate. This is quite unusual, as crowns, especially of this impressive size, are usually salvaged in many individual parts and then assembled. As connecting pieces are often missing, it was and is customary to insert the crowns completely into a quiet, generously trimmed support plate. The transitions between the original plate (lower – like an implant) and the support plate above it (higher) are then usually concealed in the area of the tapering arms by concave curved transitions. Not so in this case. The plate lies in one plane and the crown shows no signs of internal bonding. However, even in this piece it was not possible to completely avoid using plates that are not naturally bonded but have been attached. Towards the stem, the crown is bordered by plates that originate from the find layer but are not naturally adjacent to the fossil. Masterfully executed in the Hauff workshop, this transition is not visible to the naked eye.

Sold on behalf of a customer.

The colony-forming driftwood sea lily: Seirocrinus subangularis from Holzmaden

The Seirocrinus subangularis is an absolute showpiece and one of the best-known fossils from the famous Posidonia Shale formation (Lower Jurassic, around 180 million years ago) of Holzmaden. Contrary to their name, crinoids are not plants, but fascinating sea creatures that are related to starfish and sea urchins. The finds from Holzmaden are of inestimable museum value, often in the form of huge slabs called the “Swabian Medusa Head”.

Biology and lifestyle

Seirocrinus has the typical structure of a sea lily: a stalk consisting of hundreds of small “poker chips” (stalk members) and a crown with acalyx (calyx) and numerous tentacles. The animals were passive filter feeders that used their fine, feather-like arms to filter tiny food particles from the ocean current.

The outstanding characteristic of Seirocrinus was its pseudoplanktonic way of life. Unlike most crinoids, which were rooted to the sea floor, Seirocrinus attached itself in large colonies to driftwood logs drifting through the Jurassic Sea. In this way, they were able to use zones with stronger currents to filter feed efficiently. Specimens have been found with stem lengths of over 15 meters, while the crown itself measured “only” 20 to 30 centimeters.

The special feature of the Holzmaden finds

The fossils from the fine-grained, low-oxygen shale of Holzmaden are known worldwide for their spectacular preservation. In the case of Seirocrinus subangularis, not only the robust stem limbs but also the filigree, finely branched arms are often perfectly preserved. The unique taphonomic conditions prevented decomposition and made it possible to preserve them in detail, often together with the original driftwood on which they were hanging, which is extremely rare.

Finds of Seirocrinus slabs are captivating in their aesthetics and often show dozens of individuals whose arms remained parallel – an indication that the arms were held together by a kind of “Velcro mechanism” to prevent them from becoming entangled in the water. The fossils are also often partially transformed into gold-colored pyrite, which gives them a special aesthetic appeal.

Holzmaden Conservation Site: A window into prehistoric times

This detailed preservation is thanks to the unique depositional environment in the Jurassic Sea, which made Seirocrinus a “Fossil of the Year” (2018). A specimen from Holzmaden is therefore an impressive document of a unique, suspended way of life and an exquisite exhibit for any sophisticated palaeontological collection.